In other words, being mentally tough means that no matter how brutal the circumstances—whether it’s your 14th hour running through a desert in temperatures well over 100F or you’re halfway through a 400-rep workout that includes pull-ups and single-leg squats—you’re able to withstand the pain and suffering and perform to the best of your skills and talents, with a good time, high place, or even a win.

As psychologists debate the roles of genetics, environment, and learned skills in determining mental toughness, they do agree (along with athletes and coaches) that high levels of mental toughness are associated with athletic prowess and success. In fact, mental toughness (or “grit”) may be the defining factor between finishing at the front of the pack and not finishing at all.

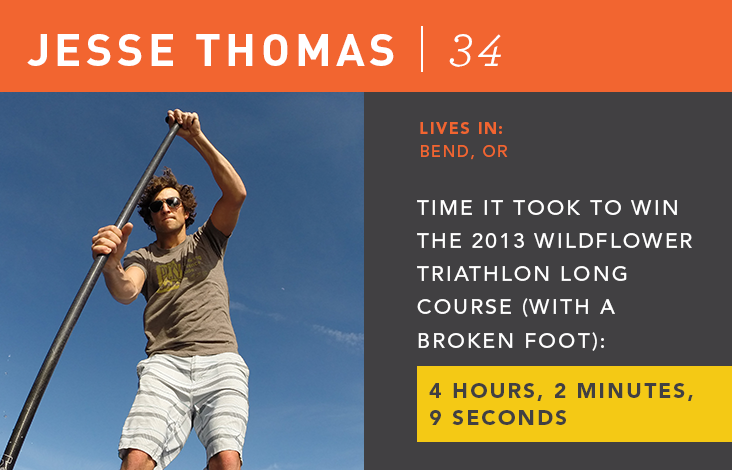

To better understand how mental toughness can help someone run through a desert for seven days straight, complete 400 grueling reps in a mere 25 minutes, or win a half-Ironman triathlon with a broken foot (yes, really), we spoke to some of the toughest athletes on the planet and asked them to reflect on how they conceptualize, cultivate, and strategize for their mental game. Here's how they manage to withstand the most grueling circumstances—and win.

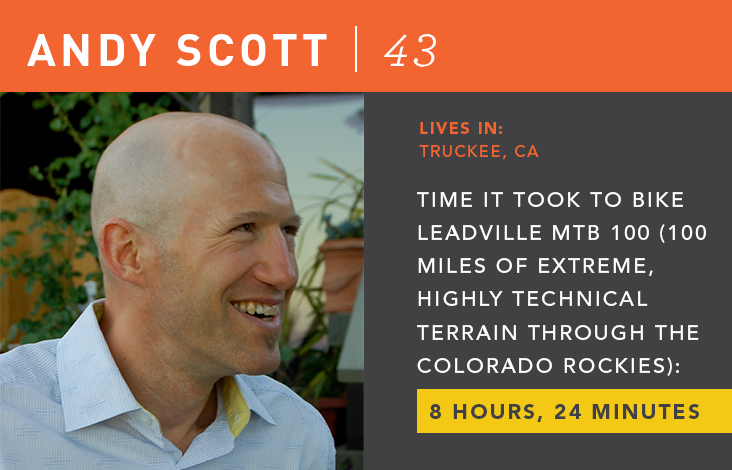

Andy Scott, Ultra-Endurance Mountain Biker and Ski Mountaineer

Though Andy Scott is not a professional athlete (no big deal; endurance mountain bike racing and ski mountaineering are hobbies for the California-based businessman), he's competed in the Leadville Trail MTB 100—a high-altitude, 100-mile race that takes mountain bikers through the Colorado Rockies across extremely technical terrain. Despite being crashed into by another rider during the race and getting thrown off his bike and into a rock garden, Scott finished in eight hours and 24 minutes, (32nd in his division and fast enough with a earn him a gold trophy belt buckle for the prestigious sub-nine hour finish.

As a ski mountaineer, he’s climbed up and skied down some of the largest, most remote, and challenging mountains in the western United States (like the time he climbed California’s 14,000-foot Mt. Tyndall just after a snowstorm that brought with it high-speed winds and an intimidating wind chill).

Mental toughness is…

…when you, your body, the competition, nature, or the environment has the best of you so that you’re physically tapped out and need to figure out how to pull something out of yourself… not in a robotic way—in a way that’s mentally aware and engaged. It’s not just the ability to keep moving but to keep doing it in a way that’s engaged and competitive in the environment you’re in, whether that’s competing against the clock or other human beings. It’s easy when you feel good physically. It’s when that physicality leaves you.

…when you, your body, the competition, nature, or the environment has the best of you so that you’re physically tapped out and need to figure out how to pull something out of yourself… not in a robotic way—in a way that’s mentally aware and engaged. It’s not just the ability to keep moving but to keep doing it in a way that’s engaged and competitive in the environment you’re in, whether that’s competing against the clock or other human beings. It’s easy when you feel good physically. It’s when that physicality leaves you.

Why you're stronger than you think you are

What you’re physically capable of in an endurance environment is more determined by your mental strength than your physical capabilities… your body can go beyond what your physical perceptions of tiredness or fatigue are. Your brain will be telling you “You’re tired. Stop.” It’s trying to stop you from killing yourself. The mental limitations kick in before the physical limitations.

What you’re physically capable of in an endurance environment is more determined by your mental strength than your physical capabilities… your body can go beyond what your physical perceptions of tiredness or fatigue are. Your brain will be telling you “You’re tired. Stop.” It’s trying to stop you from killing yourself. The mental limitations kick in before the physical limitations.

On training for mental toughness

Visualization is a piece of the training that is incredibly important. You don’t have to do anything physically—you can be meditating or walking, anything where you’re in your mind, playing it out in advance. You’re imagining the start, the route, the competition, those points that your body is saying, ”stop,” or that you’re suffering. You’re mentally training yourself to push through those barriers.

Visualization is a piece of the training that is incredibly important. You don’t have to do anything physically—you can be meditating or walking, anything where you’re in your mind, playing it out in advance. You’re imagining the start, the route, the competition, those points that your body is saying, ”stop,” or that you’re suffering. You’re mentally training yourself to push through those barriers.

The hardest thing he's ever done physically

The most challenging thing for me… was the solo climb and ski of Mount Tyndall. There was a storm; the conditions just became overwhelming. Something about the winds at high altitude is just intimidating and mentally draining. The second piece of that is that I was alone; there are no external sources of support. I realized, “Whoa, there are no people cheering.” There’s a degree of self-sufficiency required. And then there’s the remoteness.

How he got through it

It’s probably cliché, but it comes back to core faith, and for me, that’s my family and the people that are closest to me. They are actually sitting in my head, and that’s helping bring a degree of mental clarity to the situation to ensure I don’t do anything stupid. The second thing is my training and experience. I mean, in many ways the training is harder than the event itself in terms of the hours you’re putting in. No one is cheering for you. You’re mentally training for those moments and that’s giving you the reserve to be able to say, “I’ve seen this. I’ve done this; I know I can do it because I’ve been there before.”

It’s probably cliché, but it comes back to core faith, and for me, that’s my family and the people that are closest to me. They are actually sitting in my head, and that’s helping bring a degree of mental clarity to the situation to ensure I don’t do anything stupid. The second thing is my training and experience. I mean, in many ways the training is harder than the event itself in terms of the hours you’re putting in. No one is cheering for you. You’re mentally training for those moments and that’s giving you the reserve to be able to say, “I’ve seen this. I’ve done this; I know I can do it because I’ve been there before.”

On Leadville MTB 100

This event is about redlining yourself over the course of eight hours. I started out physically and mentally fresh but I had mechanical problems with my bike, and crash mishaps and those things gradually took some physical and mental strength out of me. By the last couple of hours, you’re basically spanked, running on physical and mental empty. What that then results in—you climb inside of yourself. Endurance athletes have this term: “the pain cave.” You have to get comfortable in the pain cave. It’s a place of prolonged suffering. You know you’re going to experience it but you find a way to know that it’s not going to last forever.

This event is about redlining yourself over the course of eight hours. I started out physically and mentally fresh but I had mechanical problems with my bike, and crash mishaps and those things gradually took some physical and mental strength out of me. By the last couple of hours, you’re basically spanked, running on physical and mental empty. What that then results in—you climb inside of yourself. Endurance athletes have this term: “the pain cave.” You have to get comfortable in the pain cave. It’s a place of prolonged suffering. You know you’re going to experience it but you find a way to know that it’s not going to last forever.

Samantha Gash, Ultra-Endurance Runner

In 2010, when she was 25 years old and had one marathon under her belt, Australia native Samantha Gash took a semester off from law school to race 155 miles through the Chilean desert in the Atacama Crossing—a self-supported race in which participants carry between 15 and 30 pounds of supplies—whatever they’ll need over the course of the seven-day event—on their backs. She then went on to complete in multi-day ultra-marathons across three other deserts, making her the first woman—and youngest person ever—to complete a Four Desert Grand Slam. In other words, she completed self-supported multi-day ultra-marathons through deserts in China, Chile, Egypt, and Antarctica in one calendar year.

Having run through some of the toughest conditions imaginable (race organizers describe the deserts as some of the “driest, hottest, coldest, and windiest places on earth,”) Gash has continued her endurance racing career in events that are physically and mentally grueling, like her 235-mile solo race across Australia’s Simpson Desert, for which she ran nonstop for three days, 14 hours, and 28 minutes. To learn more about Gash, check out Desert Runners, the documentary that follows four runners (including Gash) as they compete in Racing the Planet’s 4 Desert Ultra-marathon Series. (Just use the code "GREATIST" for 10 percent off a digital download of the movie.)

Mental toughness is…

For me, mental toughness is acknowledging that very challenging moments can occur in all sports—and also in life in general—but having the capacity in a quick time frame to turn a negative experience into a positive one.

For me, mental toughness is acknowledging that very challenging moments can occur in all sports—and also in life in general—but having the capacity in a quick time frame to turn a negative experience into a positive one.

The hardest thing she’s ever done physically

In 2012 I ran nonstop for 379 km (235 miles) across the Simpson Desert in Australia. I did take 30-minute stops to change into warm clothes, lay down, and eat dinner. That was so physically demanding that I was delirious. The last 40 km was the most painful place I’ve taken my body and mind to.

In 2012 I ran nonstop for 379 km (235 miles) across the Simpson Desert in Australia. I did take 30-minute stops to change into warm clothes, lay down, and eat dinner. That was so physically demanding that I was delirious. The last 40 km was the most painful place I’ve taken my body and mind to.

The most mentally grueling moment she's experienced while racing

I think China (the Gobi March, a 250-mile race through the Gobi Desert) was the most mentally grueling—that long stage I ran with Lisa [Tamati, an ultra endurance athlete from New Zealand]. I felt so many things. The night was coming, we’d been going for 12 hours, it was really hot, and I was pretty injured. But I wanted to stick with Lisa so I was dragging myself and didn’t want to let go of Lisa.

I think China (the Gobi March, a 250-mile race through the Gobi Desert) was the most mentally grueling—that long stage I ran with Lisa [Tamati, an ultra endurance athlete from New Zealand]. I felt so many things. The night was coming, we’d been going for 12 hours, it was really hot, and I was pretty injured. But I wanted to stick with Lisa so I was dragging myself and didn’t want to let go of Lisa.

I try to focus my mind on the positive of completing. When I’m in immense physical pain, I try to dull the pain as much as possible. Once the pain enters your head (as opposed to just your body), you start to legitimize ways of pulling out. I distract myself by thinking about why I’m doing it. My body and mind is stronger than I’d ever think.

Mark Pattinson, Endurance Racing Cyclist

Mark Pattinson, 44, has been an endurance racing cyclist since 2006. He rides about 70 hours per week to stay in shape for events like Race Across America (also known as “the World’s Toughest Bike Race”) during which he will ride from California to Maryland, covering 3,000 miles—which includes 170,000 feet of hill climbs—over the course of eight to 12 days, stopping only to sleep for about two hours per night. Pattinson has completed the race twice, earning second place in 2011 and 4th place in 2013, and will take it on again in June 2014.

Mental toughness is…

It means being able to keep on performing whilst in extreme discomfort. It’s the ability to mentally overcome the brain, which is telling you to stop, and keep pushing yourself forward, even if things aren’t going well.

It means being able to keep on performing whilst in extreme discomfort. It’s the ability to mentally overcome the brain, which is telling you to stop, and keep pushing yourself forward, even if things aren’t going well.

On training for mental toughness

I prepare myself through my own experience—I’ve been in these positions before. I know that when things are bad, it will get better. It could take hours, it could take minutes, it could take days, but it will. It’s naturally in me. I’ve made it my mantra: “At times it’s so bad but it will get better.”

I prepare myself through my own experience—I’ve been in these positions before. I know that when things are bad, it will get better. It could take hours, it could take minutes, it could take days, but it will. It’s naturally in me. I’ve made it my mantra: “At times it’s so bad but it will get better.”

His strategy for getting through several days of competition

I have a distinct strategy. I break the race up by the day. I know I’m going to get up, I’m going to ride my bike, and then I’m going to do it again. When I get off my bike and go to sleep for one-and-a-half or two hours, I get up the next day to do it again. I know I am going to sleep in the dark at nighttime. I think that really helps me break the event down into pieces instead of seeing it as one 3,000-mile race.

I have a distinct strategy. I break the race up by the day. I know I’m going to get up, I’m going to ride my bike, and then I’m going to do it again. When I get off my bike and go to sleep for one-and-a-half or two hours, I get up the next day to do it again. I know I am going to sleep in the dark at nighttime. I think that really helps me break the event down into pieces instead of seeing it as one 3,000-mile race.

Stuff does go wrong—you can get a little lost or you might get a flat tire and it’s very easy to get down. But if you spend too much time being down about it, it can throw your race completely. I tell myself, “Get on with it. We’ll talk about that later. We’ll worry about that later.” There’s no point in worrying about things you can’t change. Every moment you’re not moving is time wasted. You just keep moving and talk it through with the crew. We’ve had lots of things go wrong. You have to keep yourself in a place that’s not a panic.

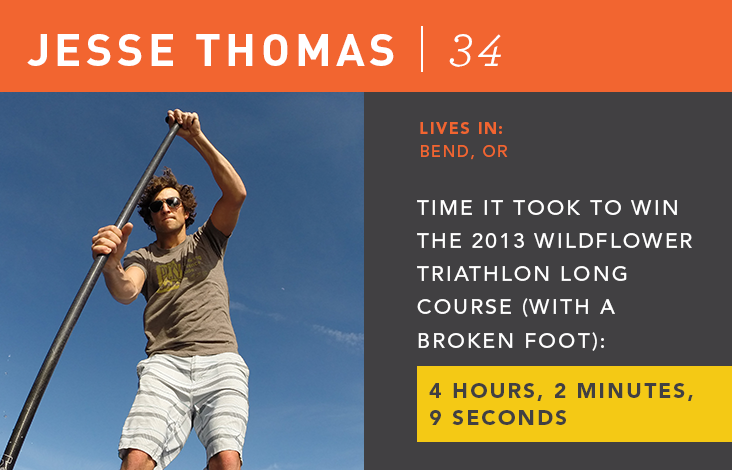

Jesse Thomas, Long Course Triathlete

After an accomplished and successful college running career (he was an NCAA All-American in the 3000m Steeplechase, a unique event that combines running, hurdling, and long jumping), Jesse Thomas took a break from racing to start a tech company. Four years later, he returned to running to give triathlons a try—and he turned out to be pretty darn good at it, even winning the USA Triathlon National Championship title for his age group in 2007. Four years later, in his first full year as a professional athlete, Jesse won his third Wildflower Long Course, making him the first male to win the event three years in a row. Thomas’ event is the triathlon long course, in which competitors complete a 1.2-mile swim followed by a 56-mile bike race, and finish with 13.1-mile run.

Mental toughness is…

I think of mental toughness as your ability to deal with pain and to process it. It’s your body’s ability and your mind’s ability—mostly your mind’s. Mental toughness could be the ability to get out of your body what your body is capable of that day.

I think of mental toughness as your ability to deal with pain and to process it. It’s your body’s ability and your mind’s ability—mostly your mind’s. Mental toughness could be the ability to get out of your body what your body is capable of that day.

The difference between “bonking” and hitting the wall mentally

You actually can hit the physical limits of what you can do, nutritionally and hydration-wise. But when you hit a nutritional or hydration wall, you bonk—you have to stop. Those physical things are kind of impossible to get through, to be honest. But I’ve hit mental walls where I’ve felt like my race is in the shit can and then somehow—through mantras, or if I pass somebody, maybe—I get this positive signal and I gain momentum, and it feels like it has some physical effect. Realistically, it’s probably a mental thing.

You actually can hit the physical limits of what you can do, nutritionally and hydration-wise. But when you hit a nutritional or hydration wall, you bonk—you have to stop. Those physical things are kind of impossible to get through, to be honest. But I’ve hit mental walls where I’ve felt like my race is in the shit can and then somehow—through mantras, or if I pass somebody, maybe—I get this positive signal and I gain momentum, and it feels like it has some physical effect. Realistically, it’s probably a mental thing.

On the mantras and mental tricks that give physical kicks

In a Half Ironman, I’m out there for four hours. I can have a bad 20 or 30 minutes, come out of it, and still have a pretty awesome race. I have go-to mantras. It’s really dorky. “You’re kicking ass!” “You’re killin’ it!” I say them out loud, almost yelling them. I’ve found that the more physical you can make them, [the better]—you’re not only saying them, you’re hearing them, too, which makes a difference. Also, a mental kick that always gives me a physical kick is interacting with the crowd in some way. When I say “Thank you!” [to someone cheering on the sidelines] or give someone a high five, I feel like I can literally feel tangible energy connecting from those people to me.

In a Half Ironman, I’m out there for four hours. I can have a bad 20 or 30 minutes, come out of it, and still have a pretty awesome race. I have go-to mantras. It’s really dorky. “You’re kicking ass!” “You’re killin’ it!” I say them out loud, almost yelling them. I’ve found that the more physical you can make them, [the better]—you’re not only saying them, you’re hearing them, too, which makes a difference. Also, a mental kick that always gives me a physical kick is interacting with the crowd in some way. When I say “Thank you!” [to someone cheering on the sidelines] or give someone a high five, I feel like I can literally feel tangible energy connecting from those people to me.

On training for mental toughness

I definitely visualize before every race. I try to divide it up into as many key points as I can. I set goals and trigger points and I try to tie as little of it to external factors as possible. So, I’ll say, “At halfway through I want to feel like this and I want to make a move that increases my output by 10 percent.” Those kinds of things make me feel like I am on a race plan regardless of where I am in my overall goal.

I definitely visualize before every race. I try to divide it up into as many key points as I can. I set goals and trigger points and I try to tie as little of it to external factors as possible. So, I’ll say, “At halfway through I want to feel like this and I want to make a move that increases my output by 10 percent.” Those kinds of things make me feel like I am on a race plan regardless of where I am in my overall goal.

One thing I’ll say is that deep tissue massage has become my mental training. In order for it to be effective you can’t block it out or keep it from penetrating. You have to relax as much as possible and accept the pain. I tried the same thing with my track workouts—instead of pretending the pain wasn’t there, I’d accept as much of the pain as I could and make a conscious decision that my body can handle the pain. I can make my body hurt more than it hurts right now and that’s okay. That approach has made me a tougher athlete and [made me] capable of dealing with more pain.

The most physically grueling event he's ever done

At Wildflower Triathlon last year, I broke my foot. It started to hurt three miles into the race. I’d won the last two years in a row and no one had won three in a row, so it was a big deal for me to be there. I was battling head-to-head for the win. As soon as I crossed the finish line I was limping and could barely walk. I definitely think the adrenaline helped. Endurance athletes will be able to do that. My job is to basically process and deal with pain and I’ve spent however many hours a day for however many years dealing with pain so your tolerance goes up like crazy.

At Wildflower Triathlon last year, I broke my foot. It started to hurt three miles into the race. I’d won the last two years in a row and no one had won three in a row, so it was a big deal for me to be there. I was battling head-to-head for the win. As soon as I crossed the finish line I was limping and could barely walk. I definitely think the adrenaline helped. Endurance athletes will be able to do that. My job is to basically process and deal with pain and I’ve spent however many hours a day for however many years dealing with pain so your tolerance goes up like crazy.

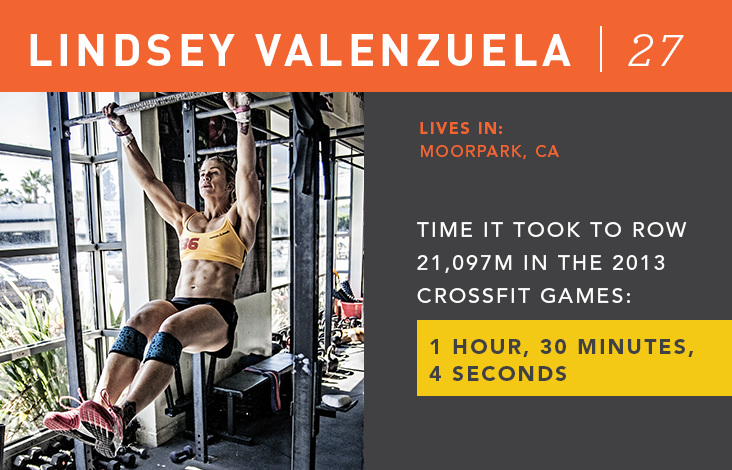

Though it’s not an endurance sport per se, elite CrossFit athletes push their bodies and minds to extreme limits in order to qualify for and then compete in the CrossFit Games, the sport’s annual competition in which the top 51 athletes from all over the world compete in a series of workouts that take place over three days. The two winners are named the Fittest Man and Woman on Earth.

Lindsey Valenzuela has climbed to the top of the sport, finishing the Games in 34th place in 2011, ninth place in 2012, and second in 2013. This means that as CrossFit and the Games have grown in popularity—drawing athletes who are increasingly strong, fast, and tireless—and workouts have gotten more grueling each year, Valenzuela continues to not just keep up, but to improve, dominating competition in her region (southern California) as well as in the Games. CrossFit fans know her for embodying her one-word motto, “Believe,” and for her infectious and spirited whoops and war cries.

Mental toughness is…

It basically means being able to overcome outside circumstances—negativity and whatever obstacles you have going on in your life at the moment—to focus on the task at hand. It’s easier said than done.

It basically means being able to overcome outside circumstances—negativity and whatever obstacles you have going on in your life at the moment—to focus on the task at hand. It’s easier said than done.

The toughest workout she's ever done

Physically, the Camp Pendleton workout at the 2012 CrossFit Games (700-meter ocean swim, an 8-km bike ride across technical terrain and soft sand, and an 11.3-km run up and down steep hills). I was in pretty good shape, but not as good as I’m in now. The workout felt never-ending.

Physically, the Camp Pendleton workout at the 2012 CrossFit Games (700-meter ocean swim, an 8-km bike ride across technical terrain and soft sand, and an 11.3-km run up and down steep hills). I was in pretty good shape, but not as good as I’m in now. The workout felt never-ending.

And the most mentally grueling workout...

The Row from last year’s CrossFit Games. [Athletes rowed a half-marathon—that’s right, 13.1 miles—on stationary erg machines. Valenzuela earned a 5th place finish in the event, after one-and-a-half hours of rowing]. I had tunnel vision. I took one water break and you know the game Fish? I played that in my head and kept thinking “I’ve been through way worse.” I’d look at the screen [giant scoreboards showed each athlete’s progress as they rowed] to see how much I had done and I'd think, “I’ve already done this much, I can do this much more.”

The Row from last year’s CrossFit Games. [Athletes rowed a half-marathon—that’s right, 13.1 miles—on stationary erg machines. Valenzuela earned a 5th place finish in the event, after one-and-a-half hours of rowing]. I had tunnel vision. I took one water break and you know the game Fish? I played that in my head and kept thinking “I’ve been through way worse.” I’d look at the screen [giant scoreboards showed each athlete’s progress as they rowed] to see how much I had done and I'd think, “I’ve already done this much, I can do this much more.”

On completing SEALFIT Kokoro Camp, a three-day mental toughness training that simulates US Navy SEAL Hell Week

I tried to find the right mixture of what’s driving me—the “why.” It’s sometimes a struggle. I wanted to honor my grandfathers who were in the service, and most importantly, I wanted to prove myself wrong. I wanted to prove I was capable of more than I thought I was capable of. I wasn’t going to give up on it. I was going to keep going no matter how hard it got.

I tried to find the right mixture of what’s driving me—the “why.” It’s sometimes a struggle. I wanted to honor my grandfathers who were in the service, and most importantly, I wanted to prove myself wrong. I wanted to prove I was capable of more than I thought I was capable of. I wasn’t going to give up on it. I was going to keep going no matter how hard it got.

A part of what they wanted us to understand [at Kokoro Camp] is that we can do more than we think our bodies are willing to do. The body is going to be the first thing to go. At SEALFit, you’re going to hurt, your feet are going to be raw, you’re going to be tired and hungry, but if your mind can keep you going, you can do incredible things.

On her mantra, “Believe,” which is tattooed on her wrist

It just means: What is your goal? What do you want to accomplish? You have to earn it. You have to get it. I say that to myself. I say, “Feed your courage dog.” Don’t feed into your fears or worries or concerns. You have to feed into your positive thoughts—those are the ones that are going to get you through.

It just means: What is your goal? What do you want to accomplish? You have to earn it. You have to get it. I say that to myself. I say, “Feed your courage dog.” Don’t feed into your fears or worries or concerns. You have to feed into your positive thoughts—those are the ones that are going to get you through.

article shared from greatist.com by Sally Tamarkin

No comments:

Post a Comment